Che cos’hanno in comune un fuoco che non brucia, un terreno che diventa più fertile e un clima che forse possiamo ancora salvare?

La risposta sta in un materiale oscuro e poroso, nato dal calore ma fatto per resistere al tempo: il biochar.

Immaginate un carbone che, invece di dissolversi in fumo, rimane nel suolo per secoli. Non è carbone da ardere, ma carbone che custodisce carbonio. Un paradosso? Forse sì. Eppure è proprio qui che la scienza ci invita a guardare più da vicino.

Un enigma nella giungla

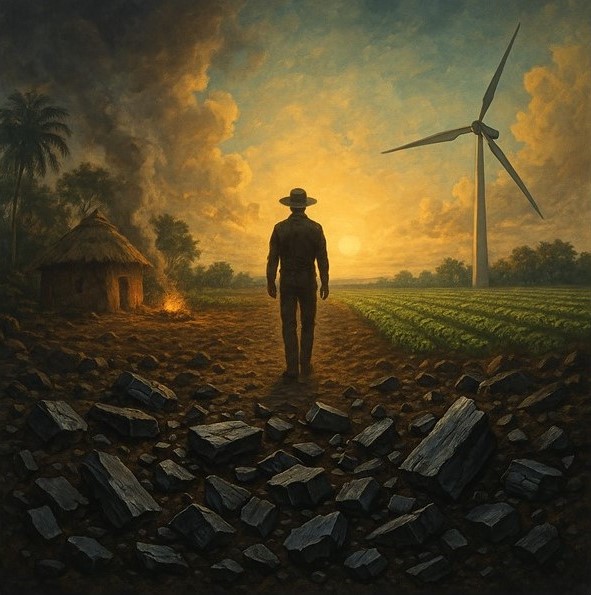

Tutto comincia in Amazzonia. Quando i primi archeologi e pedologi iniziarono a scavare nella foresta pluviale, trovarono qualcosa di inatteso: macchie di terra scura e fertile che si distinguevano nettamente dal rosso povero degli Oxisols circostanti. Gli indigeni la chiamavano “Terra Preta do Indios”, la “terra nera degli indios”.

Com’era possibile che suoli notoriamente poverissimi e instabili, incapaci di trattenere nutrienti, ospitassero invece zone in cui le piante crescevano rigogliose?

Negli anni Duemila, studi pionieristici di Bruno Glaser e colleghi mostrarono che quelle terre nere contenevano fino a 70 volte più carbonio nero rispetto ai suoli circostanti. Non un carbonio qualsiasi, ma il prodotto della combustione incompleta di biomassa: charcoal, carbone vegetale. Non il fuoco distruttivo degli incendi, ma quello controllato dei focolari domestici, dei forni di cottura, delle pratiche agricole precolombiane.

Dalla leggenda alla scienza

La Terra Preta non era un fenomeno naturale. Era la traccia lasciata da comunità indigene che, 1500–2500 anni fa, avevano imparato a trasformare residui di cucina, legno e scarti organici in un suolo fertile e duraturo. Non slash-and-burn, la bruciatura che divora foreste e libera CO₂, ma slash-and-char: un modo per intrappolare carbonio e costruire fertilità.

Quel carbone, altamente aromatico e stabile, sopravvive nel suolo per secoli. Con il tempo, l’ossidazione ne arricchisce i bordi di gruppi carbossilici, che aumentano la capacità di trattenere nutrienti. È così che un materiale apparentemente inerte diventa uno scrigno di fertilità, capace di sostenere colture ben oltre il tempo degli indigeni che lo produssero.

Ed è da questa eredità che nasce la parola che oggi usiamo: biochar. Non più soltanto un reperto archeologico, ma una tecnologia da ripensare in chiave moderna.

Il biochar oggi

Il nome potrebbe sembrare una trovata di marketing, ma non lo è. È il termine scelto dalla comunità scientifica per indicare il materiale carbonioso ottenuto dalla pirolisi di biomasse di scarto – legno, residui agricoli, perfino sottoprodotti animali – e applicato volontariamente al suolo per migliorarne la qualità.

Perché dovremmo interessarcene?

Perché sappiamo che l’aumento della temperatura globale è dovuto alle attività umane, e abbiamo bisogno di strumenti nuovi per rallentare la corsa dei gas serra. Il biochar, se ben prodotto e ben usato, sembra offrire proprio questo:

- intrappolare carbonio nei suoli, togliendolo dall’atmosfera;

- migliorare la struttura dei terreni, rendendoli più fertili e meno erodibili;

- adsorbire sostanze tossiche, ripulendo acque e suoli inquinati;

- modificare il pH, favorendo la crescita delle piante.

Tutto questo non è teoria: sono osservazioni sperimentali che hanno acceso un entusiasmo globale. Ma… funziona sempre così?

I segreti nei pori

Il punto è che il biochar non è mai uguale a sé stesso. Dipende dalla biomassa di partenza, dalle temperature di pirolisi, dalle condizioni di produzione. Alcuni biochar sono stabili e utili; altri, invece, si degradano più in fretta o rilasciano ciò che dovrebbero trattenere.

E allora come capire quali biochar funzionano davvero?

È qui che entrano in gioco le tecniche che uso nel mio lavoro. Con la risonanza magnetica nucleare (NMR) possiamo osservare il comportamento dell’acqua confinata nei pori del biochar: come si muove, quanto resta intrappolata, quali interazioni crea con ioni e contaminanti. In pratica, possiamo ascoltare la “vita interiore” di un pezzo di carbone.

Queste informazioni ci permettono di costruire modelli più affidabili e di distinguere tra biochar efficaci e biochar illusori. È un lavoro di pazienza, ma necessario: se vogliamo usare il biochar come strumento di sostenibilità, dobbiamo capire i suoi meccanismi più profondi.

Esprit de char

Il National MagLab ha raccontato parte di questa avventura in un articolo dal titolo evocativo: Esprit de char. “Lo spirito del carbone”: un nome che rende bene l’idea. Perché il biochar non è solo un materiale tecnico, è un ponte tra passato e futuro. Un carbone antico, ma con un compito nuovo: aiutarci a riscrivere il rapporto tra l’uomo, il suolo e il clima.

E domani?

Sarà allora il biochar la chiave di un’agricoltura davvero sostenibile?

Non dobbiamo illuderci: non è una bacchetta magica. Non basterà da solo a risolvere la crisi climatica o a rigenerare i suoli impoveriti. Ma può essere uno strumento potente, se usato con intelligenza.

Forse, in fondo, l’“esprit de char” non è altro che questo: la memoria di un fuoco che, anziché consumare, ha creato. Un fuoco che ancora oggi può insegnarci a trasformare l’ombra in risorsa, il carbone in futuro.

Per approfondire:

- Esprit de char – National MagLab

- Glaser et al. 2001 – The Terra Preta phenomenon

- Agronomy 2021 – Biochar e dinamiche dell’acqua

- Molecules 2025 – Caratterizzazione strutturale del biochar

- Applied Sciences 2023 – Proprietà fisico-chimiche e applicazioni

- Agriculture 2022 – Biochar e fertilità dei suoli

E qualche mio vecchio post divulgativo:

Esprit de char (English)

What do a fire that doesn’t burn, a soil that becomes more fertile, and a climate we might still save have in common?

The answer lies in a dark, porous material, born from heat yet made to resist time: biochar.

Imagine a charcoal that, instead of turning into smoke, remains in the soil for centuries. Not charcoal for burning, but charcoal that locks carbon away. A paradox? Perhaps. And yet this is precisely where science invites us to look closer.

A jungle enigma

It all begins in the Amazon basin. When the first archaeologists and soil scientists dug into the rainforest, they found something unexpected: patches of dark, fertile earth standing out against the poor, reddish Oxisols all around. The locals called it “Terra Preta do Indios”, the “black earth of the Indians.”

How was it possible that soils known for being extremely poor and unstable, unable to hold nutrients, could instead host areas where plants thrived so vigorously?

In the early 2000s, pioneering studies by Bruno Glaser and colleagues revealed that these black soils contained up to 70 times more black carbon than their surroundings. Not just any carbon, but the product of the incomplete combustion of biomass: charcoal. Not the destructive fire of wild burns, but the controlled fires of domestic hearths, cooking stoves, and pre-Columbian farming practices.

From legend to science

Terra Preta was not a natural phenomenon. It was the trace left by indigenous communities who, 1,500–2,500 years ago, had learned how to turn kitchen waste, wood, and organic residues into fertile, enduring soil. Not slash-and-burn, the practice that devours forests and releases CO₂, but slash-and-char: a way to trap carbon and build fertility.

That charcoal, highly aromatic and chemically stable, survives in soil for centuries. Over time, oxidation enriches its edges with carboxylic groups, increasing its nutrient-holding capacity. In this way, an apparently inert material becomes a treasure chest of fertility, able to sustain crops long after the indigenous people who created it had disappeared.

And it is from this legacy that the word we use today was born: biochar. No longer just an archaeological curiosity, but a technology to be reimagined for modern times.

Biochar today

The name may sound like a marketing gimmick, but it isn’t. It’s the term chosen by the scientific community to define the carbon-rich material produced by the pyrolysis of waste biomass – wood, agricultural residues, even animal by-products – and deliberately applied to soil to improve its quality.

Why should we care?

Because we know that global warming is driven by human activity, and we need new tools to slow the race of greenhouse gases. Biochar, if properly produced and applied, seems to offer exactly this:

- locking carbon into soils, keeping it out of the atmosphere;

- improving soil structure, making it more fertile and less prone to erosion;

- adsorbing toxic substances, helping to clean polluted soils and waters;

- altering soil pH, favoring plant growth.

This isn’t theory: these are experimental findings that have sparked worldwide enthusiasm. But… does it always work that way?

Secrets in the pores

The truth is that biochar is never the same. It depends on the feedstock, on the pyrolysis temperature, and on the production conditions. Some biochars are stable and effective; others degrade quickly or release what they were meant to retain.

So how do we know which biochar really works?

This is where the techniques I use in my research come into play. With nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) we can observe how water behaves inside biochar pores: how it moves, how long it remains trapped, how it interacts with ions and contaminants. In practice, we can listen to the “inner life” of a piece of charcoal.

Such information allows us to build more reliable models and to distinguish effective biochar from illusory ones. It’s painstaking work, but essential: if we want biochar to be a true sustainability tool, we must first understand its deepest mechanisms.

Esprit de char

The National MagLab told part of this story in an article with an evocative title: Esprit de char. “The spirit of charcoal”: a name that captures the essence. Because biochar is not just a technical material—it’s a bridge between past and future. An ancient charcoal with a new task: to help rewrite the relationship between humans, soils, and climate.

And tomorrow?

So, is biochar the key to truly sustainable agriculture?

We shouldn’t fool ourselves: it’s no magic wand. Biochar alone won’t solve the climate crisis or restore degraded soils. But it can be a powerful tool – if used wisely.

Perhaps, in the end, the “esprit de char” is nothing more than this: the memory of a fire that, instead of consuming, created. A fire that still today can teach us how to turn shadow into resource, charcoal into future.

Further reading:

- Esprit de char – National MagLab

- Glaser et al. 2001 – The Terra Preta phenomenon

- Agronomy 2021 – Biochar and water dynamics

- Molecules 2025 – Structural characterization of biochar

- Applied Sciences 2023 – Physicochemical properties and applications

- Agriculture 2022 – Biochar and soil fertility

And some of my earlier blog posts (in Italian):